design of democracy (3)

barriers to entry

We have tried to regulate away the positive feedback gain and have failed simply because it is impossible to decouple elected office from the accumulation of power. If the accumulation of power cannot be decoupled from elective office (and I discussed why this was impossible to do in my last post), then this accumulated power becomes a high barrier to entry for would be challengers.

We have tried to regulate away the positive feedback gain and have failed simply because it is impossible to decouple elected office from the accumulation of power. If the accumulation of power cannot be decoupled from elective office (and I discussed why this was impossible to do in my last post), then this accumulated power becomes a high barrier to entry for would be challengers.

Our democratic ideals say our candidates should be competing for votes based on the ideas they propose (their electoral platform) and their leadership track record (or the level of trust the public places on them). The reality though is that today's media soaked culture rewards high media exposure with high name recall -giving the advantage to candidates who get in the news often (be it political or entertainment news).

Incumbents have the advantage of a high profile job that gives them natural exposure in the news media. This is wholly part of the positive feedback gain. This media exposure along with access to social and political networks presents a high barrier to entry that would be challengers must overcome if they are to be on competitive footing against incumbents.

How do we compute the relative cost of this barrier? What toll does it put on our electoral system?

Investments and pre-investments

Running for an elective position requires resources. The higher the post, the more the resources are needed to get elected to the position. If you are running for president, you are competing for 30M-35M votes, and depending on the size of the field (number of candidates) will need to garner somewhere in the region of 12M to 17M votes. To get elected to the Senate, you will need to garner at least 12M votes. To get elected to the House of Representatives requires anywhere from 25,000 to 200,000 votes (depending on the district) .

You can monetize these voter numbers to see the cost of a campaign (i.e. P1=voter, then you will need P12M minimum to campaign for the senate). This is, at least in theory, relatively easy to do during the actual campaign period. We know of course that campaigning to get elected begins way before the official campaign period and so incumbent politicians who want to get re-elected will devote resources in advance of elections. This is where the comparative advantage - given by the positive feedback gain -comes in.

When the incumbent gets a CDF outlay for her district (and plasters her name all over the project), when she appears in public to give speeches or cut an inaugural ribbon, when she donates to community events, when she appears in the news, or when she glad hands local leaders -she is "pre-investing" resources in getting re-elected. She is also building name recall.

Likewise, a new candidate "invests" in brand creation and name recall when they elevate their public profile (via TV shows, or movies, or appearances in local fiestas, or being cited in the news) so as to get name recall.

Unlike funds spent on a campaign, the pre-campaign "investment" in name recall is nearly impossible to monetize. We need to find a way to measure the relative effect of these investments to see their effect on electoral contests.

Cost of voter acquisition: c as a function of v and r

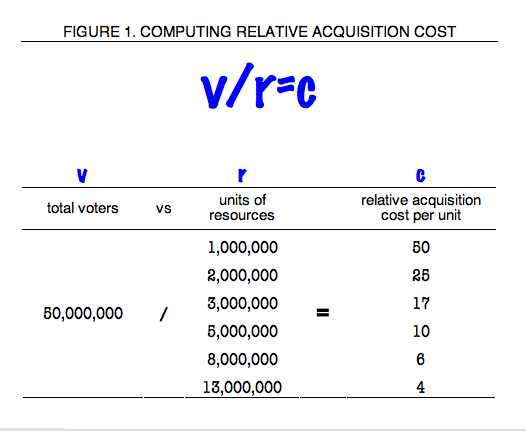

We can attribute a per unit cost (c) to acquiring a voter (i.e. -getting a vote) by expressing it as the ratio of total votes needed (v) vs. total resources expended (r), such that:

The cost of acquisition "c", expressed as a per unit cost, allows us to compute the relative advantage of investing more vs. less resources in an electoral campaign. You can view it as the relative marginal cost of acquiring another vote or the relative "friction" of the system against a candidate. (The lower the number, the lower the marginal cost or the lesser the friction.)

We can use this relative unit "c" to grasp how high the barrier to entry is. It also allows us to illustrate the system dynamic.

Figure 1 (click image for larger view) shows that in a electoral contest over 50 million votes, investing 12M more units gives a candidate a relative advantage of -46c vs. a candidate expending 1M units. In other words, the marginal acquisition cost of another voter is 4c units for a candidate spending 13M, while it is 50c units for a candidate spending only 1M units.

The system dynamic means that (at least in large populations) more "r" gives you a lower "c."

An incumbent, with 4 to 6 years of media exposure along with access to resources and social and political resources, has easily invested huge amounts of "r" giving him a lower "c". The longer an incumbent stays in office, the more "r" is naturally invested in making "c" lower.

The system dynamic drives new candidates to expend a similar magnitude of resources to achieve a competitive "c". It also means that only persons who already have a high "r" have any chance of being considered as candidates. (We know this instinctively and we recognize "dark horse bets" and celebrate the unlikely success of "cinderella" candidates.)

The logic of getting celebrities to run for public office makes total sense given this system dynamic. Because celebrities come with built-in media exposure (read: pre-investment" -not to mention a strong "brand" based on their media typecast), a popular celebrity would have already expended high volumes of "r" which gives the celebrity a lower "c."

Next: Attempts to level the playing field by regulating "r"